采访 INTERVIEWS

The beginning of June saw a rare convergence of American musical talent visiting China, with both the Juilliard Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra leapfrogging their way across the country. Why the Juilliard Orchestra played the A-list halls and the Philadelphia Orchestra the less prestigious venues is a question for another time. A more pressing issue involves programming, and particularly, the unbridled recurrence of a composition that stands singularly for Chinese music history in the Twentieth Century: the Yellow River Piano Concerto.

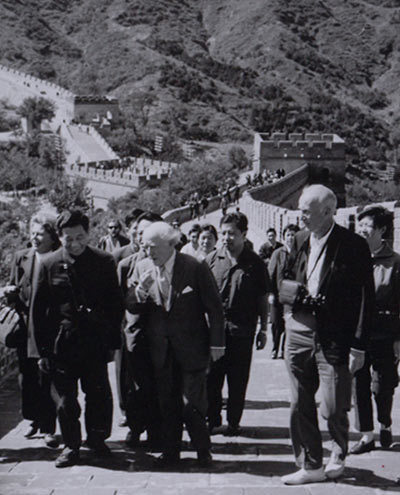

Born as Xian Xinghai's Yellow River Cantata in a cave in a Yan'an cave during the Sino-Japanese War, the Concerto evolved into its more-or-less present form when Madame Mao ordered pianist Yin Chengzong to create a work of appropriate political fervor during the high tide of the Cultural Revolution. The concerto headlined the Philadelphia Orchestra's first historic tour of China in 1973; it then disappeared from the Chinese stage for the decade following Mao's 1976 death, although it retained a sort of radical chic for orchestras abroad, enraptured by its derivativity in much the same way art critics have recently regarded some of China's more famous Western-influenced painters.

On the June 1 “Concert of Friendship” at the National Centre for the Performing Arts, the Juilliard Orchestra performed the inevitable “Moon Reflected on Second Fountain,” followed by the Yellow River Piano Concerto with 15-year-old Chinese-born Juilliard Pre-College prodigy Peng Peng as soloist. The very next night, less than a mile away in the Minzu Gong (or Nationalities Palace), marking the 35th anniversary of their historic first visit to China, the Philadelphia Orchestra performed, in a closed concert for the Chinese leadership, what else? “Moon Reflected on Second Fountain” and the Yellow River Piano Concerto, with the equally inevitable Lang Lang.

With so much time, money and energy invested in bringing these sensational ensembles to China, why was the Beijing concert-going public subjected to two consecutive concerts with almost identical programming? Do cultural bureaucrats take pleasure in pressuring the international musical community to make obeisances to official modern Chinese musical culture through the imposition of these works? Are these programmers simply lazy? Have they and the Chinese audiences not outgrown their “revolutionary” tastes? Is this someone's idea of a big post-modern practical joke, along the lines of, “We had our era of a repertoire restricted to a handful of works now, foreign orchestras, it's your turn!” Or is it the fault of the international orchestras who don't take the time to research other repertoire, with the Chinese presenters playing along?

I went in search of answers in Beijing's musical community, asking both Chinese and expatriates. This is what I learned; music-loving readers are invited to sort out the sincere from the sarcastic according to their own taste and temperament.

_“Some prefer the original oratorio from which the Tchaikovsky/Rachmaninoff-plagued soloistic concerto was derived. It's not something listened to for formal value, but some moments are revelatory; it's a very earnest, pure work reflecting the truer sides of the liberation of the masses, with melodies worthy of Stephen Foster and Jerome Kern. As a whole art work, though, the kitsch factor and girth can prove more than a little unwieldy.”

“The Yellow River Concerto captures the true spirit of the Chinese people through their struggle and strife, better than any piece of music written in the same medium before or after.”

“Change = bad. Until the whole music system here is changed, Yellow River will continue to be considered the pinnacle of concerti, right alongside The Butterfly Lovers. The people who could have written the next Yellow River all left the country because they were under the thumbs of their superiors. Now that they have become successful, they should come back and shake things up. The public at large is ready for it.”

“The old traditions are dying, withering away, ever so slowly. The best place to see this is the recording studios. Gradually, you hear more and more outside influences, albeit sometimes very subtly, in the best composers. They retain the ”Chinese Style“ (read: I-IV-vi-ii-V-I) but occasionally though in something that makes it listenable.”

“The problem here is that they are taking Mahler to the extreme. The folk song permeates EVERY work that comes out. Not that this is bad. However, where is the original thought? Most composers' ideas of development result in nothing more than tedious themes with variations. They are all pandering to the idea that if they don't give the people what they want to hear, then they will be out of work.”

“The Chinese are very proud of their compositions and want the international music world to know their work.”

'I think the Chinese presenters asking foreign orchestras to play this music has more to do with marketing to conservative musical tastes than with patriotism."_

Chinese composers winced when asked about the Yellow River Concerto, but, enjoying increasing creative freedom and international success, they were more optimistic about the future. How about it, tongzhimen, time for one of China's newly rich to commission new Chinese music for China's new virtuosi. They deserve it, and so do we.